By Katie Leggett and Greg Paulson

In this post we'll tackle the question of how many Greek New Testament manuscripts there are using the latest information in the NTVMR. We'll explain how Greek New Testament witnesses are currently registered in the Liste and some of the complexities of counting manuscripts.

The work of cataloguing all known Greek New Testament manuscripts worldwide is a massive endeavor that has been going on for many years. The Kurzgefasste Liste (for more on the history of the Liste, see here) was designed to offer a systematic list of all known Greek New Testament manuscripts and to make them available as potential witnesses for use in critical editions and more widely for scholarly research. Greek New Testament manuscripts are designated with a Gregory-Aland (GA) number and their codicological and paleographical features like date, contents, writing material, script, lines, columns, and dimensions are catalogued.

Just since 2019, an additional 167 Gregory-Aland numbers have been added (2 papyri, 3 majuscules, 81 minuscules, and 81 lectionaries.[1] These numbers would be even higher if we also included the dozens of additions to the Liste which were not given a new GA number but were identified as parts of manuscripts already entered therein. While the Liste aims to offer a census of available witnesses of the Greek New Testament, it is far from exhaustive. It's important to keep in mind there are still more manuscripts we aren't yet aware of. The Liste is constantly in flux. We are very grateful for the support of scholars, librarians, and curators who continue to collaborate and inform us of unregistered manuscripts.[2]

We have also been in the process of cleaning up the Liste by identifying manuscripts that were unknowingly entered twice, combining folios that belong together, and removing manuscripts that never should have been entered in the first place because, for example, they have no New Testament content or were entered without enough information to identify them.

While some might find it disconcerting that so many entries have been stricken from the Liste, this purging process has actually been going on for many years. In the first edition of the Liste (1963), Kurt Aland described this "Bereinigung" and its importance in detail; he continued this reduction process into the second edition in 1994 as well.[3] The desideratum has never been to simply add as many manuscripts as possible but rather to offer the most accurate representation of the available manuscript evidence. We recognize there have been many inconsistencies over the years about what qualifies for inclusion (e.g. Psalms and Odes, prayer books, ostraca, supplements, manuscripts with virtually no information to identify them again, etc.). We are in process of creating more sensible and transparent criteria for what manuscripts should be removed and what will be included in the future.

Counting Complexities

Some of the factors that make tallying manuscripts difficult have been discussed elsewhere but we'll briefly address a few of these issues here.[4]

First, throughout its history, the Liste (or its predecessor inaugurated by Gregory) has included diverse New Testament witnesses such as lectionaries and other liturgical books, amulets, ostraca, and even patristic works; these have been divided between the four main Liste categories of: papyri, majuscules, minuscules, and lectionaries. (But of course, the distinctions between categories are not always clearcut.) Under minuscules one also finds catenae, but not lectionaries even though they are written in minuscule script. Under lectionaries were Psalms and Odes (which will no longer be added) as well as other liturgical books like euchologia.[5] Even if we compare two "complete" New Testaments, a full continuous text of Mark will contain all 16 of its chapters, but a complete lectionary might only contain four or five chapters of Mark (none of which are even a complete chapter). Yet a lectionary will still be considered "complete" for what it was intended for (in this case, liturgy on Sundays). This means when we speak of "manuscripts" we mean a wide range of witnesses with Greek text of the NT, and these of course have varying worth for critical editions, dating from the late second century to the eighteenth century.

Second, numerous manuscripts have gone missing over the years or have been destroyed. We're still working out the best practice for how to deal with these. Should they be counted, especially if there are no images? For the moment if we have good reason to believe a manuscript no longer physically exists (but have not yet confirmed), we have decided to tag it in the NTVMR with the feature called "Manuscript Destroyed." There are currently 56 manuscripts in the Liste tagged as “Manuscript Destroyed”. The majority of these were held at Mega Spileon Monastery in Kalavryta and the Skete of Saint Andrews on Mt. Athos. Sometimes we are pleasantly surprised to rediscover a manuscript presumed destroyed. This was the case, for example, with 0229 formerly housed at the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana in Florence. While the 1963 Liste noted it was destroyed, it was, in fact only badly damaged and is now housed at the Papriological Institute in Florence.[6] Another example is the four leaves of 0106 held at the University Library in Leipzig that were listed as "Kriegsverlust" and long assumed to have been destroyed in WW2. However, they were recently rediscovered in the Moscow State University Library.[7]

Another concern is what to do with manuscripts that have long been missing. When we don't know the current location of a manuscript, we list it under "location unknown" (formerly called "Besitzer unbekannt"). There are currently 105 manuscripts in this category, but these are certainly not all the same! Some are here because they were recently auctioned or sold. Numerous manuscripts have landed in private collections, which makes them tricky to keep track of. This was the case for 2805 which was held in a private collection in Athens until it was sold on Christies in 2013. Through a gracious tip[8] we found out it had been purchased by a private collector in New York.

Unfortunately, this proves the exception as private buyers often do not want to be identified, especially if their manuscript has a problematic provenance.

Other manuscripts in "location unknown" like those in Damascus have been missing for over 100 years. Despite our best efforts, we've not be able to verify where these are.[9] But manuscripts that have been missing for decades do occasionally turn up again. Many of the manuscripts held at the Kosinitza Monastery near Drama, Greece were looted during WWI and have been missing since then. Several of these have been located again in recent years including 1424 and 1429 which have been returned to Drama.[10] Just last month we discovered another Kosinitza New Testament manuscript: L2378 that has ended up in Sydney. (Here is a presentation about this lectionary. At timestamp 6:24 the origin of the manuscript and its theft from Monastery Kosinitza is narrated.)

In 2021, GA 2853 was removed from "location unknown" when it was discovered to be the same as 2892 owned by the Van Kampen Foundation and housed in Orlando.[11] Likewise we discovered 2343, whose location has been unknown since at least the 1963 Liste, was at the Walters Art Museum under GA 2375. These few examples illustrate why we never give up hope of a manuscript turning up again after we've lost track of it.

Adding to the complexity of counting manuscripts is the fact that one entry, that is one GA number, can represent a single fragment with just a few verses like 0317 (pictured below).

Or one GA number can represent a rather voluminous codex, such as L351, with over 300 leaves (pictured below).

While this fragmentary nature is well known for papyri (and perhaps majuscules), this is often overlooked when it comes to minuscules and lectionaries. In fact, approximately 27% of lectionaries have 50 folios or less and 10% of minuscules have 50 folios or less.

Another matter that can make understanding data in the Liste confusing is that there isn't always a one-to-one correlation between an entry in the Liste and a single artefact. That is, one GA number doesn't necessarily correspond to one physical manuscript or a single shelf number at a holding institution. It is possible for multiple artefacts scattered throughout the globe to share a single GA number. This is the case with L2434, which has a current total of 48 leaves dispersed throughout 26 locations.[12] Here is the list of locations of L2434 in the NTVMR.

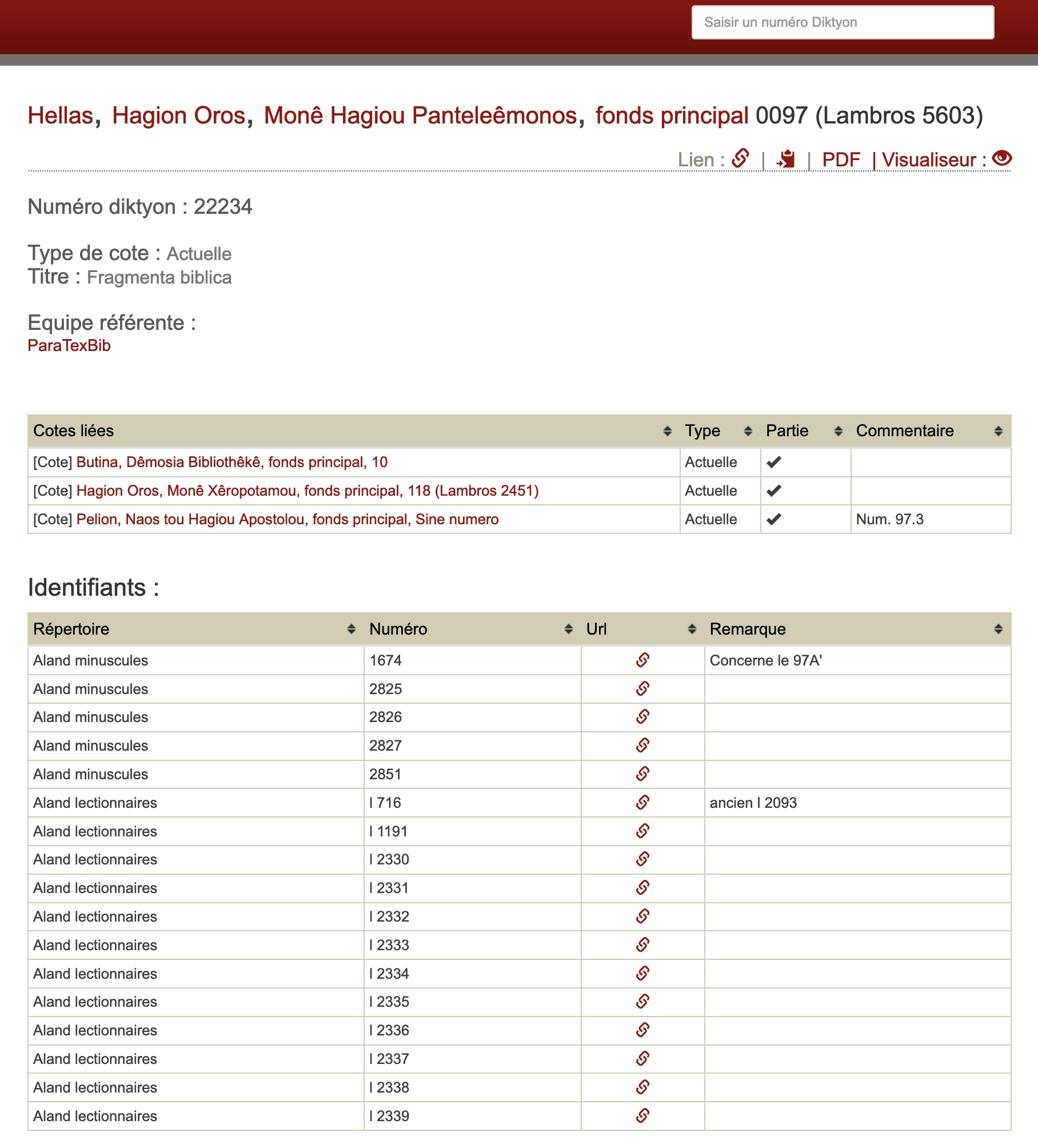

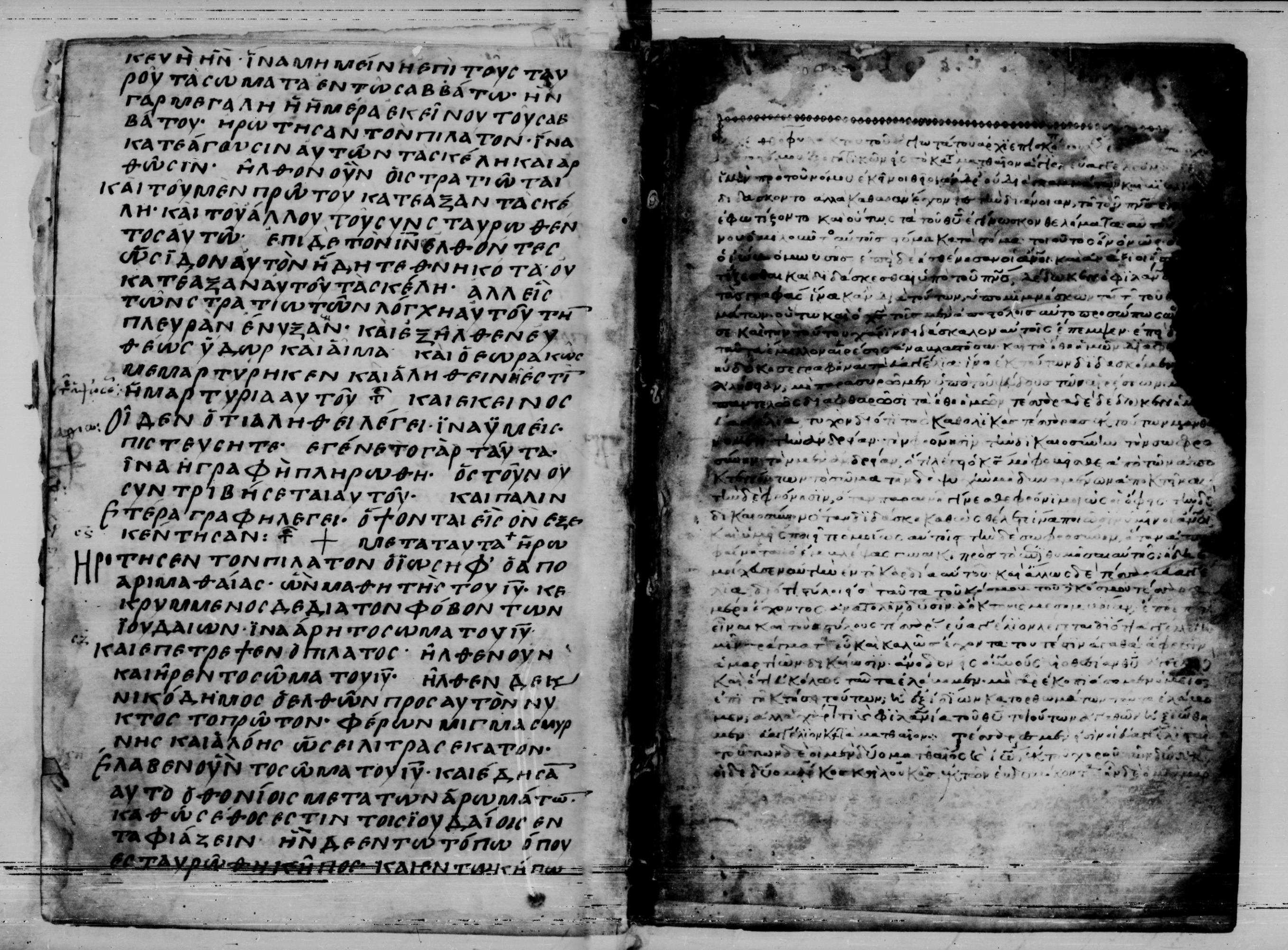

Or it often happens that a single artefact will be assigned multiple GA numbers, such as Panteleimon Monastery 97, which has been given 17 Gregory-Aland numbers! (See its entry in Pinakes below.)

Each part of the artefact was given a separate entry because it had unique features which could not be subsumed under a single GA number.

Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana Gr. Z. 10 has two GA numbers, 209 and 2920, because fol. 1-381 were originally Gospels, Acts, Catholic Letters, and Paul, and later a manuscript of Revelation was combined with it, becoming fol. 382-421 in the same codex. These two portions of Gr. Z. 10 are from different centuries, have a different line count, and the script is different (with 2920 resembling 205 according to Gregory). These were clearly originally two separate artifacts and were not intentionally made to be bound together.

Thus, one artefact can be given multiple GA numbers if the physical features (e.g. date, columns, writing material) deviate so greatly from the other parts that it must be catalogued in the Liste as a separate entry to record these distinctions. Here is an example from Barb. Gr. 521, where GA 054 and 392 are bound in the same codex (see below).

And depending on the purpose of an artifact, a shelf mark could represent a collection of material, such as Paris, Suppl. Gr. 1155, which has 11 GA numbers. As you can see in these images, folio 4v Suppl. Gr. 1155 (GA 063) is distinct from the following folio 5r (GA L352) (see below).

Then there are supplemental portions of manuscripts.[13] If the supplement was originally part of another manuscript and was later torn out and bound together with another manuscript, in the past the rule of thumb was that it was assigned a new GA number.[14] Some supplements were created specifically with the intention to replace the missing text in a manuscript, and these are not normally given a separate GA number (e.g., fol. 89-96 in GA 2542).[15] However, this isn't always possible to know for certain, and doesn't change the fact that part of a manuscript may have distinct paleographical and codicological features that cannot simply be subsumed under one GA number. For new entries when a manuscript contains features that varies substantially from the rest of the manuscript,[16] we will consider on a case-by-case basis whether to give that portion a new GA number. We must be careful about assigning GA numbers ad absurdum and inflating the Liste beyond what is manageable or useful.

So, a manuscript scattered across various holding institutes may share a single GA number or portions of a single artefact may be assigned multiple GA numbers. Palimpsests add yet another layer of complexity since the same pages of a single artifact can be assigned two GA numbers. This is the case with Cambridge University Library, Ms. Add. 10062. The undertext is 040 (Codex Zacynthius) containing portions of the Gospel of Luke, and the overtext is L299 with daily readings from the four Gospels.

Thus, one GA number does not always correspond to a single manuscript or artefact but rather designates a distinct paleographical and codicological witness of the New Testament text. This distinction is useful at times for understanding the data in the Liste and working with manuscripts in the real world. For example, if someone wanted to view Greek New Testament manuscripts at the Herzog August Library in Wolfenbüttel, Germany they would look in the Liste and see eight entries. But if they asked the librarian for eight New Testament manuscripts there might be some confusion since the library has only five artefacts with text of the NT with five different shelf numbers (or six if you count their manuscript of Psalms with Odes!). In other words, how the INTF catalogues manuscript witnesses in the Liste (that is, based on text critical features) may be different than how holding institutions themselves catalogue their manuscripts. In the case of Wolfenbüttel, one of their artifacts was given a second GA number for the book of Revelation, and two of their manuscripts contain palimpsests with New Testament text.

With so many factors that complicate the task of counting manuscripts, it's no wonder that obtaining an accurate tally of Greek New Testament manuscripts is often seen as a fool's errand and the desideratum is round numbers or a gross estimate that may be much higher or lower than the actual number. We fully recognize that the data in the Liste is a work in progress and there are still inconsistencies and errors to be resolved. There are still far too many manuscripts registered which we know very little about. It is likely there are still dozens of duplicate entries and fragmented/separated manuscripts that belong together that need to be identified.[17] Nevertheless, we believe the Liste offers the best data available about the current Greek New Testament manuscript evidence and we strive continually to make it more accurate.

In light of the complexities mentioned above, we are convinced that rather than trying to ascertain how many New Testament manuscripts we have, a more useful question—and one which we can answer by utilizing the NTVMR—is how many New Testament witnesses have been catalogued in the Liste to date. By utilizing the NTVMR, this is relatively easy to find out.

Without further ado, here are the current tallies:

Customizing the Results

The NTVMR also offers users the ability to sort through the data and generate lists which eliminate certain kinds of manuscripts. Providing customized parameters can refine search results. It is possible, for example, to eliminate all manuscripts tagged as "Manuscript Destroyed," or "Presumed Missing," or other liturgical books or commentary manuscripts (including catenae).

For example, if you wanted to know how many minuscules there are that do not have a commentary, you can do the following search in the NTVMR:

Enter "3" as the ID in the "Manuscript Num." field

Select the feature "Commentary"

Check the box "Does not have"

Select the feature "Removed"

Select "Display"

Check the box "Does not have"

(Or click here to perform this search—you can see the search parameters in the URL.)

And you’ll discover there are 2,236 minuscules in the Liste that do not have a commentary.

Another example: if you want a tally of all lectionaries, but do not want to include ones tagged as "Other liturgical books," this can be easily done as well.

Or you can add together all destroyed manuscripts with ones presumed missing, and subtract this number from the total number of manuscripts, which results in 5,541 manuscripts.

Therefore, user can generate a more sparse or refined list of New Testament witnesses depending on their interests or research purposes.

In closing, the current number of entries in the Kurzgefasste Liste, 5,700, is only a snapshot in time; it will surely be outdated soon—probably even before you’ve finished reading this. There are certainly still more duplicate entries to be found, more manuscripts waiting to be assessed, and more discoveries to be made. While we continue to hope for new discoveries, particularly as exciting digitization efforts are underway in places like Sinai and Athos, it's also possible the current numbers will decrease as more entries are combined and we continue to prune results so we can offer the most accurate and reliable inventory of the Greek New Testament manuscript evidence.

[1] Some of these lectionaries were inserted in the free numbers L1581–L1598 and L1596 (see here).

[2] Here a special word of thanks is due to the tireless efforts of Georgi Parpulov who has informed us of dozens of new additions, many of which result from Birmingham’s Catena project.

[3] See Aland, "Einführung," in the Liste (1st ed., 1963), 12ff.

[4] See J. Raasted, Review of the 1963 Liste, Libri 16 (1966): 75–76; J.K. Elliott, Review of the 1994 Liste, NovT 39 (1997): 85–87; D.C. Parker, An Introduction to the New Testament Manuscripts and Their Texts (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 38–46.

[5] We are waiting for a full-scale analysis of the liturgical books catalogued in the Liste before we undertake any efforts to sort through which manuscripts in the lectionary category should be removed.

[6] This error seems to stem from translating the Italian "distrutto" as "destroyed" instead of "badly damaged." See Iginio Crisci “La collezione dei papiri di Firenze” in Proceedings of the Twelfth International Congress of Papyrology, ed. Deborah H. Samuel, ASP 7 (Toronto: Hakkert, 1970), 93

[7] R. Ast, A. Lifshits, and J. Lougovaya, "Codex Tischendorfianus 1, Rediscovered and Revisited," ZPE (2016): 141-160.

[8] Thanks to Brent Niedergall for this information.

[9] For some background on these missing fragments see here.

[10] L1240 and 2856 both stolen from Kosinitza are now in Sofia, Bulgaria. It is also highly likely that this manuscript, sold in 2004 through Sotheby’s, is Kosinitza's L1244.

[11] Thanks to Hugh Houghton for his assistance in this discovery. Unfortunately, the whole Van Kampen collection seems to have now gone underground with the closing of the Holy Land Experience in Orlando, FL.

[12] Some of these leaves were in the Liste under four different GA numbers. After Andrew Patton identified them as originally belonging to one lectionary, dismembered by Otto Ege, they were consolidated under the GA number L2434. Since then numerous leaves have been added. For more watch the video here.

[13] Dealing with supplements has admittedly been handled in different ways throughout the years and there are many inconsistencies in the Liste concerning which supplements get their own GA number and why. Hundreds of manuscripts have anomalies, e.g. in contents, line count, different hands etc. and recording these goes beyond the scope of a "kurzgefasste" list.

[14] This is generally observable when the contents of the biblical text overlap (e.g., 278 and 2898), although this is rare—more often a lectionary and a minuscule will share the same codex; or Revelation (which often circulated by itself) will be added to the end of an existing codex.

[15]The most famous exception to this rule is Vatican gr. 1209 (i.e. GA 03 and 1957).

[16] How much divergent material a manuscript should contain and how many features must be different from the main part of the manuscript depends on several factors. As a rule of thumb, if only one or two features vary, we will insert a brief footnote to explain which features are different. If we are dealing with three or more divergent features, we consider assigning a new number. For example, a manuscript contains 50 pages written three centuries later with a different line count and a different number of columns than the main manuscript, then the case could be made that these folios represent a unique instantiation of the New Testament text which merit a new GA number. This is our criteria going forward. The INTF does not currently have the time and resources to review all previously entered manuscripts for supplements that may meet these criteria.

[17] This is especially true for the lectionaries. We are currently in the process of uploading microfilm images for lectionaries in the NTVMR which will make it much easier to identify duplicate entries or folios that belong together.

Personal Blogs

Personal Blogs  Recent Bloggers

Recent Bloggers